Mission Statement:

"To advance through research, education and symposia, an increased public awareness of the Cape Fear region's unique history."

Poplar Grove Plantation

at

Scott's Hill

Cape Fear Historical Institute Papers

Origins and Ownership of Poplar Grove

Elizabeth McKoy’s “Early New Hanover County History”

(1973) informs us that the background of Poplar Grove and

its vicinity is the large tract of land “patented to Maurice Moore

in the year 1729. Much of Maurice Moore’s land was inherited

by his son James Moore, and James Moore and his wife

Ann Moore sold [tracts] to Cornelius Harnett . . . [in 1767].”

The plantation was already producing peas, corn and beans,

and the original house overlooked Futch’s Creek (Fryar, pg. 4].

McKoy continues: “Cornelius Harnett did not hold his

splendid expanse of land and water for many years. In 1784

his wife [Mary Holt Harnett] was a widow and it was she

who sold the land to Francis Clayton. This was 3 February 1784.

The Executors of Francis Clayton are ordered by his

Will to sell his property. So Henry Urquhart and Henry Toomer

in the name of the executors sold this [Topsail Sound] property

which Harnett had named Poplar Grove. The whole of it was

bought by James Foy – the expanse of land, the mansion

house and the banks lying to the southward and in the sight

of the Mansion House. Francis Clayton had had possession

only from 1784 to before 1795. James Foy the same year sold

part of this to William Nichols – who already owned the

Watts land to the east.”

Author Alfred Moore Waddell notes this regarding the

vicinity of Poplar Grove: “Francis Clayton owned other lands

besides this expanse between [Topsail] Sound and Rich Inlet

Creek and Perry’s Creek, [a] branch of Rich Inlet Creek . . .

His other holding was up the North East Branch of the Cape

Fear River, and it again was land with a Moore background –

was indeed Moorefields.” (Waddell, pg. 56-57)

According to author Waddell, Clayton Hall was the residence

of Francis Clayton and located just above today’s Rocky Point;

after his death the plantation was sold to Col. Samuel Ashe,

son of Governor Samuel Ashe. Colonel Ashe was the

grandfather of Capt. S. A. Ashe, the pre-eminent

North Carolina historian and author.

Francis Clayton was a political leader in the area who served

as a Wilmington Borough Member of the Provincial Congress

in 1774, as well as a member of the Wilmington Committee

of Safety. The latter group included local leaders such as

Col. James Moore, Samuel Ashe, Henry Toomer, Peter Mallett,

William Purviance, Robert Howe, Cornelius Harnett,

William Hooper, Sampson Moseley, Samuel Swann,

Thomas Bloodworth, John Devane, James Wright,

Bishop Dudley, John Ashe, and John Quince.

Francis Clayton and John Walker in 1779 seized and

jailed British naval officer George Carey “who came in a

vessel to the Cape Fear under a flag of truce, to distribute

manifestoes offering terms of settlement to the people

without regard to continental or State authorities.”

The earliest known resident of this region, Maurice Moore

had laid out the settlement of Brunswick Town on the lower

Cape Fear River in June of 1726, and sold the first lot in that

new town. By 1729 there were sufficient residents in the

area for the General Assembly to create New Hanover County.

Maurice Moore “was the second son of Royal Governor James

Moore of South Carolina, who first came to the Albemarle

country to aid in the suppression of the Indians in 1713,

and after making his home there for about ten years, removed

to the Cape Fear, having induced his two brothers, Roger

and Nathaniel, living in South Carolina, to unite with him

in founding a new settlement.” (Waddell)

Records of this Topsail Sound Property:

“170 acres, James Moore & Ann his wife to Cornelius Harnett;

40 acres, James Moore & Ann his wife to Caleb Mason

(Part of a larger tract devised by the late Colonel Maurice

Moore to James Moore).” Also, “628 acres, Poplar Grove . . .

Henry Urquhart & Henry Toomer to James Foy, Jr.,

(land sold by Mary Harnett Widow & Executor of Cornelius

Harnett to Francis Clayton, 3 February 1784, and by

him by will 2 October 1790 devised to be sold.)” (Early

New Hanover County Records, Elizabeth F. McKoy,

1973, page 27)

James Foy, Jr. of Poplar Grove Plantation:

James Foy, Jr. was born in 1772 at Sugar Maple Plantation

in Onslow county, the son of James Foy Sr. and Elizabeth

Ward. He married Henrietta Rhodes in 1794, she the daughter

of Col. Henry Rhodes and Mary Elizabeth Woodhouse. Col.

Rhodes was a Revolutionary officer who fought at the battle

of Moore’s Creek Bridge in late February, 1776 alongside

James Foy Sr. – Col. Rhodes later served in the North

Carolina House of Commons and Provisional Congress

delegation. James Foy Sr., a veteran of King’s Mountain,

Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse, received a hand wound

at the battle at Moore’s Creek (Redcoats on the River, pg 100).

James died on 14 March 1823 at Poplar Grove; wife

Henrietta passed away on 9 April 1840.

Scott’s Hill in the Revolutionary War Period:

During the British occupation of the Wilmington area in

1781, patriot resistance was found in the direction of Scott’s Hill.

In July of that year, about 18 militia men under Major James

Love were surprised by Major James Craig and 65 of his

redcoats at Rouse’s Tavern about eight miles north of Wilmington

(today’s Ogden) and below Scott’s Hill. Eight of eleven patriots

were killed by Craig's redcoats.

A valuable commodity during the American Revolution,

salt production operations were suspended when the British

returned to the area in 1780. In June 1781 the North Carolina

House passed a resolution to raise a company of

“Light Horse be immediately raised . . . for the protection

of the Salt Works on Topsail Sound . . . and other such duty

within the District of Wilmington as the commanding officer

of the said District shall direct.” The very same action would

take place some 80 years later and against a different enemy.

President George Washington embarked on a Southern Tour

in early 1791 and was in North Carolina by mid-April.

He spent the evening of 23 April at Robert Sage's Inn on

the New Bern Road just south of today's Holly Ridge, and

continued his journey to Wilmington the morning of the 24th.

The President’s party passed by Poplar Grove by early

afternoon and was met by Wilmington’s Light Horse Guards

at the aforementioned Rouse's Tavern, and escorted to town.

Joseph Mumford Foy

Son of James and Henrietta (Rhodes) Foy and the oldest of six

children, Joseph Mumford (1817-1861) was born in the

Futch’s Creek plantation house on 25 May 1817.

James married Mary A. Simmons Tuesday evening, 19 November

1839, and their union produced four children: David Hiram (1840),Henrietta (1844), Joseph T. (1850), Henry Simmons

(1853), and Francis Marion (1855).

By 1860 James Foy had built Poplar Grove into a productive

plantation raising peas, corn, beans and swine, and worked

by sixty-four slaves, or “hands” as they were referred to in

that period. Those hands lived in twelve houses

built on the property.

Politically a Unionist as were most conservative North Carolinians

of that time, Joseph would have disagreed with the political

secession of his State in 1861, but also would not endorse

a federal invasion of sovereign States to coerce them into

remaining within the Union against their will. Joseph died on

1 April 1861 at age 43, shortly after the war began.

Joseph and Mary Foy’s Plantation House – The Architecture:

The current plantation house was constructed in 1850 after

a fire reportedly destroyed the original home located near

Futch’s Creek, where it was close to water transportation.

The new home was built near the New Bern plank road,

a wooden road extended from the foot of Market Street

in Wilmington to the Onslow county line (Pender County

was carved from New Hanover in 1875) and facilitated the

movement of produce and goods - for a toll of ten cents.

Plank roads, also known as “farmers’ railroads,” were

agitated for in the 1850’s by farmers who wanted

all-weather roads to transport produce to market or

the nearest rail line. Construction of a plank road

required a graded and settled roadbed about eight

or ten feet wide, heavy timbers laid length-wise,

and heart pine planks laid perpendicular.

The assembly was then covered with sand

and opened to traffic.

Heavily damaged from the hauling of artillery during

the War Between the States, it was later paved with shells.

A 12-room, 4284 square foot Foy home is representative

of about 20 percent of the Greek Revival architectural style

which feature a one-story front porch with square classical

columns not extending the full height of the façade, as well as

the common low-pitched hip roof. The front doorway has

sidelights and a full transom which is common of this type,

as well as 6-pane window sashes.

Raised on a full brick basement, the large two-story house

features a center-hall plan, straightforward Greek Revival interior

finish, and double tiered rear porch linked by an exterior stair.

The high basement and rear porch configuration are designed

to deal with the hot, humid coastal climate. The basement

opens beneath the rear porch into a brick-paved service

area akin to examples in Wilmington, giving access to

a rear terrace surrounded by the domestic outbuildings.

Notable outbuildings include a large brick smokehouse,

a smaller brick building described as a kitchen, a frame

carriage house, frame tenant house, sheds and other

structures. The house and outbuildings are restored –

offering a rare glimpse of coastal plantation architecture

of the 19th century.

The Greek Revival style was dominant in American domestic

architecture from about 1830 through 1850, and often referred

to as the National Style. The Greek War for Independence

(1821-1830) aroused great sympathy in the US and

triggered American interest in classical architectural form.

The previously dominant Adam Style of architecture

had lost popularity after the War of 1812.

As Joseph Mumford Foy is cited as the designer of the home,

he could have utilized a carpenter’s guide and pattern book

of the style, one of the most influential was Asher Benjamin’s

“Practical House Carpenter; the Builder’s Guide,” and Minard

Lafever’s “Modern Builder’s Guide.”

Wartime at Foy Plantation:

After the death of James in 1861, Mary and the youngest

children left Poplar Grove probably to refugee in Sampson County,

leaving the care of the plantation with an overseer. By 1864,

her next oldest son Joseph T. Foy is managing the

plantation at age 17 while she remains in Sampson County.

A note on plantation overseers:

Most large plantation owners in North Carolina employed

overseers (or superintendents) to assist in the management

of the labor and crops.

As early as 1818 a group of planters in Brunswick County

urged the State to make it compulsory for owners of ten

or more slaves to “employ some white male person to

superintend and oversee” the Negroes.” In 1830 the

General Assembly did pass such a law, making it applicable

only to New Hanover and Brunswick counties.”

Planter and Overseer

It was strenuous work and not highly remunerative,

and customary to furnish the overseer lodging and pay

him in one of three ways: money wage payable [in late

1850s often $125 - $250] in notes convertible to cash;

a smaller money wage and specific amount of provisions;

or a share in the crop profit plus certain specified provisions.

On large plantations slaves worked from sun-up to

sun-down, though a well-managed plantation system

would obtain the most crop production with minimal

sacrifice of the slave’s health. The prevailing system

of slavery in North Carolina was a close relationship

between master and slave, and fully 67 percent

of slaveholders worked side by side with their labor.

Joseph & Mary A. Foy’s Children:

David Hiram Foy:

Born 27 December 1840, David was educated at local academies

and graduated from the University of North Carolina with an A.B.

(Artium Baccalaureatus with an emphasis on classical studies)

in 1861 (UNC History, pg. 207).

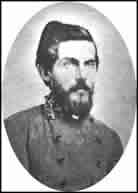

He enlisted at Scott’s Hill in 7 March 1862 for service in

a company of mounted men from New Hanover and Onslow

counties, originally named the “Rebel Ranger’s” organized

at Scott’s Hill (Nearby Onslow county provided the

“Gatlin Dragoons” as guards of their coast).

Authorized under an act passed by the Confederate States

Congress dated 21 August 1861 for local defense and special

service -- this being to guard the coastline of New Hanover

County – the "Rebel Ranger's" became known as

“Newkirk’s Coast Guard” after the unit’s first leader,

Captain Abram Francis Newkirk.

The company was mustered into Confederate States

service on 18 October 1861, reorganized, and enlistment

terms extended to three years or the war. Normally for

cavalry a recruit would provide his own horse and receive

$24 per month pay. Newkirk’s men were based at

Camp Heath, believed to be just north of Scott’s Hill

on the Sound side, and noted on an 1864 map as

an “old artillery camp.” (Keith)

While a member of Newkirk’s company he was based

at Camp Heath performing scouting and patrol duty; the

unit consisted of “4 officers, 77 men and no artillery.”

While with Newkirk's company, David was stricken with typhoid

fever (also called "camp fever") and died at home on

12 June 1862. Even this early in the war when food was

still plentiful, fatigue, poor camp sanitation and exposure

encouraged the spread of disease like malaria, smallpox

and typhoid, all which may have led to David’s

failing health. .

Common in the antebellum South was hookworm, imported

by Africans brought as slaves to North America and this

disease afflicted up to 40% in the South. Symptoms

included weakness, anemia, listlessness, shortness of breath,

bowel complaints, and susceptibility to other illness.

Also, impure waters and bad sanitary conditions in camp, as

well as poor rations and inadequate shelter and insects – led

to numerous diseases of the intestinal region. Beyond childhood

diseases and diarrhea, the danger of malaria, typhoid and scarlet

fever, and tuberculosis were present. Physicians recognized

that a good diet and rest was the best antidote for these and

often sent men home on furloughs to recover, or die.

Henrietta Foy

Born 2 March 1844, she was named for her maternal grandmother.

Raised at Poplar Grove, Henrietta married physician Joseph

Christopher Shepard on 8 May 1862. He was born on upper

Topsail Sound in 1840, the son of Alfred and Charlotte Shepard.

After attending the University of North Carolina, he studied

medicine at the University of New York and took post-graduate

studies in Paris, France. His marriage to Henrietta Foy

produced five children.

Joseph enlisted in March 1862 as a private in Lt. Zachariah

Adams Battery, and a month later appointed assistant surgeon

in the Third North Carolina Cavalry, serving as coastal guard

under Capt. Abram Newkirk, the same unit as Henrietta’s

brother, David Hiram. Joseph was then assigned to Major

Charles W. McClammy’s brigade which fought in Virginia;

in the fall of 1864 he was transferred to Fort Fisher and

appointed Post Surgeon. He attended to the wounds of

both Gen. William H.C. Whiting and Col. William Lamb

during the second battle at Fort Fisher.

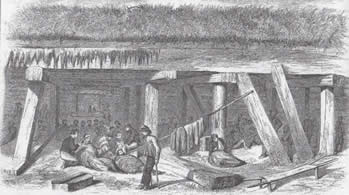

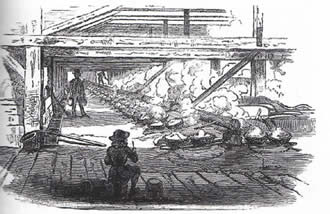

Fort Fisher Hospital

Dr. Shepard was sent as a prisoner of war to Governor's Island

and held until exchanged in March 1865. He was assigned to the Presbyterian Hospital of Greensboro, remaining there until

the South's capitulation.

Postwar, Dr. Shepard became a local “country physician”

caring for the sick and disabled in the Topsail Sound area;

in 1890 he moved to Wilmington to build a large and lucrative

practice, and was elected three times to be Superintendent

of Health for New Hanover County.

Dr. Shepard was active in the Cape Fear Camp No. 254,

United Confederate Veterans (UCV) and was appointed

Surgeon General of the UCV by both General John B. Gordon,

and General Julian S. Carr.

Dr. Shepard died 5 March 1903, both he and wife Henrietta

repose in Oakdale Cemetery. (History of NHC, DeRosset)

Joseph T. Foy:

Joseph T. Foy was born 18 September 1850. Not even eleven

years old when father Joseph died, he departed Poplar Grove

with his mother to refugee in Sampson county. He returned in

1864 to assume plantation overseer responsibilities at

Poplar Grove and excelled in this capacity.

He married Nora Dozier on 8 November 1871, became active

in local politics and played an influential role in the construction

of the Onslow and East Carolina Railroad which was

advantageous to the distribution of his plantation produce.

Aware of wartime conscription laws and Joseph being only

14 years old in 1864, Mary Foy probably allowed him to

learn and take over overseer duties as a way of avoiding

military service. The “twenty-slave” law of 11 October

1862 granted exemption of one man liable for the charge

of twenty Negroes on a farm or plantation as agriculture

sustained the Southern army.

This law was repealed in early May 1863 due to a need for

all available manpower of men under 40, though a substitute

could still be purchased. Existing too is a letter written

directly to President Jefferson Davis which asked that her

son Joseph be allowed to remain behind to care for

the “fattening hogs” and supervise 40-plus slaves

rather than be conscripted into the Junior Reserves.

Joseph’s wife Nora became the local postmaster and responsible

for handling mail for the twelve or so families residing at Scott’s Hill.

Joseph died in 1918.

Little is known of sons Henry Simmons and Francis Marion.

The Agriculture of Coastal Plantations Like Poplar Grove:

A reality of North Carolina plantations in the late 1700s was

the on-site production of virtually everything needed for human

survival: food to include beans, corn, peas, grain and fruit,

cows and hogs for dairy and meat supplies, and cotton,

then a time-consuming and laborious task to produce in

quantity, was grown sufficient to make by hand the family

clothing. Often sheep-raising for wool and mutton was

done on a small scale as well. Cattle were often raised

beyond the needs of the plantation, the meat put in casks

and salted, then sent down to Wilmington and eventually

reaching the West Indies market.

The rise of truck farming was noted in the 1840s and the Foy’s probably found a ready market for their produce in Wilmington, and a primary reason why the new plantation house was located on a direct route to both Wilmington and New Bern. Though many people in the city at that time had sufficient area on their town lots for vegetable gardens, farmers like the Foy’s might raise crops for early shipment to northern markets.

Slave Life on the Plantation:

The large-scale plantations of the South required many laborers

to plant, care for and harvest the crops, and this is the primary

reason why the British populated North America with

African slaves. Little is recorded about the individual

slaves at Poplar Grove, though their labor was of course

necessary for the success of the plantation

and the feeding of all.

Beyond their daily toil in the fields and usually alongside the master

and his sons, author Guion Griffis Johnson tells us that: “It is

a mistake to assume that the Southern slave had no money and

no means of earning any. [The] planter often rewarded his slaves

for extra work by giving them small amounts of cash.

Planters found that their slaves worked better and were more

contented if they had the means of obtaining small luxuries for

themselves: tobacco, molasses, clothing, furniture for their cabins.

It was customary to give slaves small amounts of money at

Christmas as well as at other times during the year.

[Some planters paid for crops picked over a certain amount,

a bonus system of sorts].”

There is no reason to believe that this was not the case at Poplar Grove.

Johnson continues: “It was long a custom in North Carolina to

give each slave family a small plot of ground to cultivate. Here

the slave might grow vegetables for his own table and corn for

his chickens. The master was usually willing to take any surplus

vegetables, eggs or chickens produced by his slaves and pay

a fair market price; or permit the slaves to sell

the produce elsewhere.”

John D. Bellamy’s Recollection of a Scott’s Hill Planter:

Born in 1854, Wilmingtonian John D. Bellamy (son of Dr.

John D. Bellamy) may have been speaking of Joseph M. Foy

in this excerpt from his memoirs:

“In speaking of the slave market, I once knew of a very

well-to-do planter, who lived at Scott’s Hill, who came to

Wilmington and bought a Negro woman at the auction

on Market Street. Being a fine cook, he paid five hundred

dollars for her.

One day, about six months after her purchase, he was passing

the same slave market and the auctioneer offered for sale

three Negro children; he could not get a bid for them, and

looking at the gentleman, said: “I am going to sell these

children at any price I can get. How much will you give?”

“One hundred dollars for the three,” offered the man.

The auctioneer said, “They are yours!”

They proved to be the children of the cook he had previously

bought, and the reunion brought much joy and delight. The

farmer had not the slightest idea that they were his cook’s children

when he made the bid.” (Memoirs of an Octogenarian,

John D. Bellamy, Observer Printing House, 1942, Jr., pp. 14-15)

The War Between the States and Poplar Grove:

While blockade running and Fort Fisher command the center

of attention for this region’s participation in this War, Poplar Grove

was witness to training and guard camps, as well as military

movements that passed by its front door.

It is known that Poplar Grove provided pork in bulk to

Confederate authorities and probably to help feed the

North Carolina soldiers encamped nearby. It is very likely

that local foodstuffs and meats were procured from local

plantations by the Confederate commissary in Wilmington.

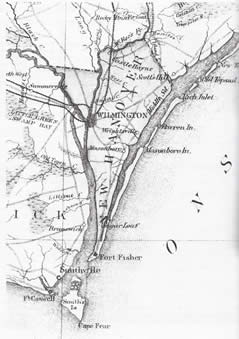

Military Operations near Poplar Grove:

The Poplar Grove-area camps included Camp Heath at

Scott’s Hill; Camp Davis of 1861-64 was reportedly located

on Middle Sound; Camp Ashe was situated on Topsail Sound;

Camps Florida and Pettigrew were both located on Topsail Island.

In addition to training troops early in the war, they would provide

a strong northern defensive line for Wilmington and detect

any enemy advances or landings.

As Mary A. Foy departed for Sampson county after Joseph’s

death in 1861 and left Poplar Grove in the hands of an overseer,

it is also probable that the plantation house rooms were available to Confederate officers in charge of troops encamped nearby.

After the enemy invasion and occupation of New Bern in the

spring of 1862, Cape Fear District commander Gen. William H.C.

Whiting fully expected an advance upon Wilmington from

that direction. Only 93 miles to the north of Wilmington,

enemy troops could easily follow the New Bern Road

passing Poplar Grove in the northeastern part of New Hanover.

To counter this imminent threat, Gen. Whiting ordered earthwork fortifications built at Virginia Creek and Holly Shelter Swamp

above Poplar Grove, and at Scott’s Hill. Just below

present-day Hampstead and three miles above Poplar Grove

on the New Bern Road the Topsail Battery of artillery

was erected to oppose the expected enemy advance.

In addition, Camp Holmes Landing was the duty station of

Adam's Battery which commanded New Topsail Inlet; this

fortification appears on the old 1864 map just north of

Topsail Creek near today's Hampstead. (Keith)

In early May 1863 General Thomas L. Clingman’s Brigade

of North Carolinian’s was ordered to move from James Island

near Charleston to Wilmington where it was posted at Camp Ashe

on Old Topsail Sound.

There the men of the Eighth and

Sixty-first North Carolina Regiments enjoyed a brief

respite near Scott's Hill. The Eighth Regiment was commanded

by Col. Henry M. Shaw of Currituck county William J. Price

of New Hanover county; the Eighth's men enlisted from

Pasquotank, Camden, Currituck, Brunswick, New Hanover,

Edgecombe, Halifax, Granville, Cumberland, Pitt, Cabarrus,

Alamance, and Rowan counties -- the latter regiment led by

Wilmingtonian Col. James D. Radcliffe and which included

men from Sampson, Beaufort, Craven, Davidson, Pitt,

Lenoir, Wayne, Johnston, Chatham, Greene, Duplin,

Wilson, Wake and New Hanover couties.

The regiments were ordered back to Charleston on 11 July

as threats of an enemy attack appeared imminent. There they

served as garrison of Fort Wagner which was under heavy

bombardment during its siege by an enemy fleet,

and a later infantry assault.

In late January 1864, General George Pickett assembled

13,000 troops and a small naval force at Kinston with which

to attack and liberate New Bern from enemy occupation.

Pickett’s strategy was a two-pronged assault – the primary

from Kinston, and a diversionary thrust would advance

from Wilmington to New Bern under General James G. Martin.

Gen. Martin’s target was Newport Barracks near Morehead

City where he would pin down the attention and resources

of the enemy located there. Though Gen. Pickett’s attempt to

liberate New Bern failed, Martin’s North Carolinian’s, consisting

of Cape Fear District garrison troops, inflicted far more damage

on enemy forces than sustained, and the feint from Wilmington

was a resounding success.

An impressive sight marching twice past Poplar Grove on the

New Bern Road, it was reported that: “Martin had moved fast,

struck hard, and routed the garrison of Newport Barracks.

He drove the Yankees back into Beaufort, killing and

wounding 17 and capturing about 80. He also captured

an enormous amount of booty including ten cannon, 200

crates of artillery ammunition, several hundred stand of

small arms, and a dozen vehicles of victuals and other supplies.”

It is noteworthy that Gen. Martin was a native of Elizabeth City;

his wife, Mary Ann Murray Read, her grandfather was

Declaration of Independence signer George Read.

The Salt Works of Topsail Sound:

From the time of settlement of the region salt became a valuable

commodity with which meat was cured and fish preserved.

On Middle Sound from Old Topsail Inlet southward to

Howe’s Point on Moore’s Creek, at least six properties,

perhaps including the Foy’s, operated salt works from 1862

until constant enemy raids had destroyed them by 1864.

Salt had become such a valuable commodity during the war

that it had no set price, it was shipped to auction in

Wilmington to obtain the highest price.

A coastal plantation owner like James Foy, Jr. may have

made salt at Poplar Grove by the evaporation method –

using wooden reservoirs with clay bottoms to produce

what was known as “Sound salt.” Salt water was

poured in, and salt eventually crystallized as the water

evaporated. He also could have utilized large pots for

boiling the salt water and using great heat to evaporate

the water, leaving raw salt as residue. This consumed a

tremendous amount of firewood and led to a great

clearing of nearby trees.

Poplar Grove Today

Poplar Grove Plantation remained in the Foy family until 1971

“when all but sixteen acres were sold off – Foy Island was

sold in 1950 and renamed Figure Eight Island. The house,

outbuildings and grounds were opened as a plantation-life

museum 1980.” (Fryar)

A popular destination for visitors

to the area in search of history to explore and experience,

Poplar Grove hosts many events throughout the year and

offers guided tours of the plantation house,

outbuildings and grounds.

Sources:

Joseph M. Foy Bible Record, Onslow County USGENWEB

Early New Hanover County Records, Elizabeth F. McKoy, 1973

Antebellum North Carolina, Guion Griffis Johnson, UNC Press, 1937

Field Guide to American Architecture, McAlester, Knoph, 1990

Historic Architecture of Eastern NC, Bishir & Southern, UNC Press, 1996

History of New Hanover County, Alfred Moore Waddell, Vol. 1, 1909

History Lover’s Guide to Lower Cape Fear, JE Fryar, Dram Tree, 2003

Alumni History of UNC, 1795-1924, General Alumni Association, 1924

Fort Fisher to Elmira, Richard H. Triebe, Coastal Books, 2010

Guns of the Cape Fear, H.J. Keith, Confederate Imprints, 2011

Memories of an Old Time Tarheel, Kemp P. Battle, UNC Press, 1945

Ironclads & Columbiads, William R. Trotter, John F. Blair, 1989

©2006 Cape Fear Historical Institute