Mission Statement:

"To advance through research, education and symposia, an increased public awareness of the Cape Fear region's unique history."

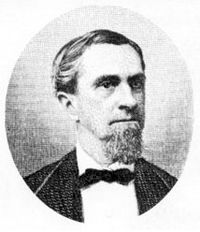

George Davis

Christian, Senator, Attorney General

Cape Fear Historical Institute Papers

George Davis

Attorney General of the Confederate States of America

Wilmingtonian, Senator, Attorney, Christian, Patriot.”

March 1st, 1820-February 23rd, 1896

Judge H.G. Conner, at Statue-Unveiling Ceremony, 20 April 1911:

“You shall bring your sons to this spot, tell them the story of his life,

of his patriotism of his loyalty to high thinking and noble living, of

his moderation in speech, his patience under defeat, of his devotion

to your City and State as a perpetual illustration and an enduring example of the dignity, the worth of a high-souled, pure-hearted Christian gentleman.”

“As you shall look on this statue, it shall be both a memorial and a lesson of the value of a citizenship which will preserve all that is good in the past, and inspire to patriotism and service in the future.”

Early Life:

George Davis was born on his father’s plantation, Porter’s Neck, in

New Hanover County on 1 March, 1820. His parents were Thomas Frederick and Sarah Isabella Eagles Davis; and among his mother's ancestors were Sir John Yeamans who recieved a Royal grant of land near Wilmington in 1665 (Yeamans became the Royal Governor of South Carolina in 1671); and John Moore, governor of South Carolina is 1700. The Davis's were originally from Massachusetts, emigrated about 1725, and were closely related to many prominent families in the region including the Lillingotn's, Ashe's and Swann's.

Davis's early education was W.H. Harden's school in Pittsboro, and he entered the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill at age 14---- graduating as class valedictorian in 1838 at age 18. He studied law in Wilmington and was admitted to the Bar Association at age 20, receiving his license to practice law the following year. His specialty in law was corporation law and he developed a wide reputation for his experise in maritime, equity and criminal law.

Mr. Davis married Mary A. Polk on November 17, 1842, she was the daughter of General Thomas Polk of Mecklenburg County and grand-daughter of Thomas Polk, one of the signers of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. The Davis' had two children, Junius and Mary Polk. He was known as a most thorough, painstaking and laborious lawyer, and in 1848 became general counsel of the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad, a position he held for the remainder of his life. Davis was known also as a splendid orator, and when nationally-known speaker Edward Everett visited Wilmington in 1859, he was introduced by Davis. Everett acknowledged Davis's oratorical ability as greater than his own.

Political Life:

In his politics, Davis was a Whig and he was highly praised for his eulogy upon the death of Henry Clay, even from Democratic journals. He was a typical conservative North Carolinian who knew the Constitutional limits

of federal power and his Whig political views included a central bank,

territorial expansion and internal improvements provided by tax dollars.

He served as director of the Bank of Wilmington. Though never holding elective office outside of Confederate government, he was nearly nominated for governor on the Whig ticket in 1848, coming within one

vote of nomination.

As a member of the Constitutional Union party and staunch Unionist prior to Lincoln's policy of coercion, the North Carolina Legislature named

Davis as one of five delegates to the Washington Peace Conference which

attempted to avert the coming fratricidal war in 1861. He had previously spoken against the secession of North Carolina and urged fellow Wilmingtonians to seek remedies for their concerns within the Union of States---presenting these views to a Wilmington assembly on December 11, 1860. The gathering passed resolutions favoring settlement of national difficulties as Davis recommended.

According to Lucius Chittenden's record (1864) of the Conference,

Davis spoke on three occasions. On the tenth day of the Conference,

a motion was made to limit debate to thirty minutes---to which

Davis replied "I think thirty minutes quite too long. Our opinions are formed. Before this time every member has determined his course of action, and it will not be changed by debate. I move to strike out the word "thirty," and insert the word "ten." He addressed the Conference on February 21, taking "the position that North Carolina was loyal to the Union, but that he fully concurred with the Southern States in the necessity of demanding constitutional guaranties; and that if these were not given, her relations were such with South Carolina and the Gulf States that, however much she might regret the necessity, she could not do therwise than to leave the Union and unite her future with those of the seceded States."

After three weeks and a lack of compromise between the sections, Davis returned to Wilmington convinced that the secession of the South was inevitable. He was asked by a group of nine city leaders to

address the people of the town, which he did on March 2, 1861. Davis

stated that he had travelled to Washington "determined to exhaust every honorable means to obtain a fair and lasting peace," but became convinced that the Union could only be preserved with dishonor to the South. He viewed the constitutional amendments presented as sectional compromise in Washington as dishonorable and inimical to North Carolina's view of

the Constitution and limits of federal authority.

"The State must go with the South," he declared.

The meeting of citizens signified its unanimous approval of Davis's conduct at the Conference (Wilmington Herald, March 4, 1861),

and from that point forward Unionist sentiment in Wilmington

all but disappeared.

North Carolina seceded from the United States on May 20, 1861 and Davis found himself elected to a two-year term as a North Carolina Senator to the Provisional Confederate Congress. During his term,

Senator Davis was considered a strong supporter of the Jefferson Davis administration and advocate for North Carolina, though tragedy struck

his home as his beloved wife Mary passed away.

Appointed Attorney-General:

President Davis appointed him Attorney General on 31 December 1863 (succeeding Thomas H. Watts) and he served in that Cabinet post until the end of the War Between the States and the dissolution of the Confederate government. He assumed the office of Attorney-General on January 22, 1864, performing the routine duties admirably and writing seventy-four opinions for Jefferson Davis's administration. His friendly advice and counsel to President Davis is seen as his most important service to the American Confederacy, and the latter genuinely respected George Davis.

The defeat of the Confederacy brought his surrender to Northern authorities at Key West, Florida, and imprisonment at Fort Hamilton,

New York until his parole in January, 1866.

Davis's son Junius, born June 17, 1845, left the Bingham Institute in Alamance county in 1863 to enlist as an eighteen year-old private in Company E, 1st Regiment, North Carolina Artillery. The son would see much action around Petersburg where he was wounded. Junius would follow his father in the practice of law (1868) and attained notable distinction in his profession.

Post-War Life:

Returning to Wilmington, Davis found himself the father of six children without a mother, and he needed to rebuild his law practice to provide an income. He then married Monimia Fairfax of Richmond to whom he had become engaged while Attorney General, and from this union two children were born. After resuming his law practise, Davis spoke out against the draconian Reconstruction measures and was a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention in 1866, designed to unite moderate Republicans and Democrats and help heal the wounds of war. He spoke out against the fanatical Republicans in April 1868 before a full house in Wilmington, and in opposition to the radical constitution they proposed for North Carolina.

Davis had become a very popular and influential citizen who continually

and successfully pressed for reforms to the radical constitution.

Davis had entertained General Robert E. Lee during the war at his home

on Second Street, and during Lee's visit to Wilmington after the war.

He became the only citizen of North Carolina ever to decline the Chief Judgeship of the State Supreme Court, offered to Davis by Governor Zebulon B. Vance in 1878. Davis continued to exercise great influence

in North Carolina’s political life and enjoyed the affection and admiration

of her citizens.

Last Public Address:

George Davis's last public address was a memorial of his former chief, President Jefferson Davis in December 1889, on which occassion he spoke without notes in Wilmington's famous Thalian Hall Opera House. Already in feeble health, George Davis spoke of his fallen President being a "high-souled, true-hearted Christian gentleman, and if our poor humanity has any higher form than that, I know not what it is."

Davis ended his last oration with:

"My public life was long since over; my ambition went down with

the banner of the South, and, like it, never rose again. I have had abundant time in all these quiet years, and it has been my favorite occupation to review the occurences of that time, and recall over

the history of that tremendous struggle; to remember with love

and admiration the great men who bore their parts in its events.

I have often thought what was it that the Southern people had to

be most proud of in all the proud things of their record? Not the achievement of our arms! No man is more proud of them than I,

no man rejoices more in Manassas, Chancellorsville and in Richmond; but all the nations have had their victories.

There is something, I think, better than that, and it was this, that through all the bitterness of that time, and throughout all the heat

of that fierce contest, Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee never

spoke a word, never wrote a line that the whole neutral world did

not accept as the very indisputable truth.

Aye, truth was the guiding star of both of them, and that is the

grand thing to remember; upon that my memory rests more proudly than upon anything else. It is a monument better than marble, more durable than brass. Teach it to your children, that they may be proud to remember Jefferson Davis."

Death of a North Carolina Patriot:

George Davis passed quietly from this life at his home on February 23, 1896 at his home at 411 North Second Street, and was laid to rest in Wilmington's Oakdale Cemetery.

The Wilmington bar of which Mr. Davis was a distinguished member for

so many years presented a resolution in his honor:

"Conservative in disposition, of sound judgement, never carried away by passion or prejudice, of large experience and familiar with all the methods of business, he was a safe, wise and judicious counsellor, as well as advocate. He was also a cultured scholar and deeply read in literature and other departments of learning. He occupied a deservedly high place in the estimation of the people of this city and State due to his pure patriotism, exalted character, incorruptible integrity and high sense of honor which made him alike eminent in

his private and public life."

(Signed) Alfred Moore Waddell, Eugene S. Martin, A.G. Recaud

The George Davis Statue:

Attesting to the depth of feeling toward Mr. Davis is the statue of him erected by the Cape Fear Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy on April 20, 1911, located at the intersection of Market

and Third Streets.

The impressive bronze statue was sculpted in 1909 by Frank H. Packer, who had direction from friends of Davis to help guide his work in creating and casting the life-image. Mr. Packer had studied under the eminent St. Gaudens and was his assistant on much of his celebrated works. The statue base incorporated a time capsule into which was place a letter from President Jefferson Davis to George Davis in 1865; James Sprunt's memorial paper, some Confederate notes and a photograph of Colonel John L. Cantwell, one of the "Immortal 600" Confederate officers held in a stockade in front of Northern artillery at Morris Island, SC in 1864.

In his 1942 "Memoirs of An Octogenarian," John D. Bellamy noted that Davis "had no toleration for new ideas. He did not believe in popular education---it was a heresy with him. He was a Cavalier, not a Puritan. On one occassion he said to me:

"This thing you boys are advocating, called progress, and the introduction of new notions is wrong; it is but a synonym for graft

and rascality."

He despised hypocrisy and hated demagoguery. He was a great stickler

for decorum. On one occassion, seeing a young lawyer with his feet elevated and resting on a table in the presence of the court and jury,

Mr. Davis came by and tapping the young man gently on the shoulder,

said to him: "Young man, no gentleman will put his feet on the table in

the presence of the court and jury."

When informed of the death of George Davis, Mrs. Varina Davis

(wife of the President) wrote that George Davis was "one of the

most exquisitely proportioned of men. His mind dominated his body, but his heart drew him near to all that was honorable and tender,

as well as patriotic and faithful, in mankind. He was never dismayed by defeat, but never protested. When the enemy was at the gates of Richmond he was fully sensible of our peril, but calm in the hope

of repelling them, and if this failed, certain of the power and will

to endure whatever ills had been reserved for him.

His literary tastes were diverse and catholic, and his anxious mind found relaxation studying the literary confidences of others in a greater degree than I have ever known in any other public man

except Mr. Benjamin. My husband felt for him the most sincere friendship as well as confidence and esteem, and I think there was never a shadowintervened between them. I mourn with you over our loss, which none who knew him can doubt was his gain."

During World War II the Liberty ship SS George Davis built in Wilmington's shipyard was named in his honor.

Sources:

Proceedings of the State Literary & Historical Assn, Conner, 1919

Memoirs of an Octogenarian, John D. Bellamy, 1942

Chronicles of the Cape Fear, James Sprunt, 1916

Dictionary of North Carolina History, William S. Powell, 1986

Wilmington During the Civil War, H.J. Beeker, Duke Thesis, 1941

©2006 Cape Fear Historical Institute