Mission Statement:

"To advance through research, education and symposia, an increased public awareness of the Cape Fear region's unique history."

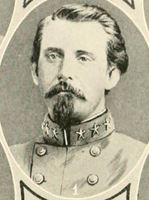

Colonel Thomas S. Kenan

Duplin Patriot, Legislator and Lawyer

Cape Fear Historical Institute Papers

Colonel Thomas S. Kenan

Thomas Stephen Kenan was the oldest son of Owen Rand

(1804-1887) and Sarah Rebecca (Graham) (1817-1871)

Kenan, born in Duplin county on 12 February 1838.

Owen was the oldest son of Thomas (1771-1843)

and Mary Rand Kenan (1781-1856), who left an

economically-depressed Duplin in 1833 with their

four youngest children for a new life in Selma,

Alabama; Owen chose to remain in Duplin.

Ancestry

Owen’s grandfather was Revolutionary War

General James Kenan (1740-1810) who commanded

the Wilmington militia district. His public career began

as sheriff of Duplin County, and he led angry Duplin

County residents to Wilmington in 1765 to protest the

Stamp Act of the British. James served in colonial

North Carolina’s general assembly as well as the

provincial Congress, and was chairman of the

Duplin and Wilmington Safety Committees that

anticipated an invasion of British troops.

James also served as a member of North Carolina’s

constitutional convention in 1788 which refused to

ratify the proposed constitution as a substitute for

the Articles of Confederation; and served again in 1789

to ratify the constitution after the Bill of Rights was inserted.

He was also a founding trustee of the University of

North Carolina. He died in 1810 after serving nine

consecutive terms in the State Senate, and the town

of Kenansville in Duplin County was

named in his honor in 1818.

Owen’s father Thomas represented Duplin County

in both houses of the State legislature, served

three terms in the US Congress, and was proprietor

of Lockland (Lochlin) Plantation with fifty African

slaves in southern Duplin. Owen emulated his forbear’s

political leadership and himself served in the State

legislature, 1834-1836. Wife Sarah was the daughter

of prominent Duplin planter-physician Dr. Stephen

Graham and inherited money, property and slaves from

her father. Owen’s daily work involved operating

both the Lockland and Graham plantations and

supervising his laborers, many being leased

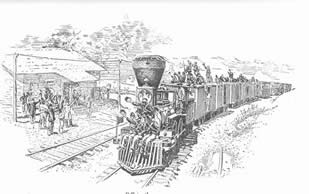

to construct the new Wilmington & Weldon

Railroad which brought prosperity

to eastern North Carolina.

Owen and Sarah’s relative wealth enabled them to

buy or construct what has become today’s Greek

Revival-inspired Liberty Hall, named for a previous

Kenan plantation. All four of their children were born

in the house: Thomas S. in 1838; James in 1839;

Annie in 1843; and

William Rand “Buck” Kenan in 1845.

Early Life and Education:

Thomas was educated at private academies in

Duplin County as his brothers and sister would be,

was sent to the Central Military Academy at Selma,

Alabama for one year, then to Wake Forest College,

and three years at the University of North Carolina

in Chapel Hill.

He graduated from the latter in the spring of 1857, studied

law at Richmond Hill, North Carolina for three years,

and established a law practice in Kenansville in 1860.

His father Owen remained politically active in Duplin,

and was elected to represent the district in

the Confederate States Congress in Richmond.

Wartime Service:

North Carolina was the last to leave the union with

the Northern States, ratifying its Ordinance of Secession

on May 20, 1861, the same date as the Mecklenburg

Declaration of Independence. The State’s withdrawal

was a foregone conclusion after Governor Ellis had

replied to the US Secretary of War’s request for

North Carolina troops to invade South Carolina:

“I regard the levy of troops made by the administration

for the purpose of subjugating the States of the South

as in violation of the Constitution and a gross usurpation

of power. I can be no party to this wicked violation

of the laws of the country, and to this war upon the

liberties of a free people. You can get no

troops from North Carolina.”

Governor John W. Ellis

North Carolina Unionists had helped keep the State

from seceding through early April, but Lincoln‘s call

for troops after Fort Sumter converted them to

secessionists. Also, Lincoln had already declared

war against the State by blockading North Carolina

ports before the Ordinance was ratified on May 20th.

Thomas had already been commanding the Duplin Rifles

military company with brother James G. on the roster.

The company was accepted for six months State service

on 15 April 1861 and assigned to the Twelfth Regiment,

North Carolina Troops (Second Regiment, NC Volunteers);

accepted into Confederate States service on 18 May 1861;

then mustered in as “Captain Thomas S. Kenan’s

Company of Light Infantry on 18 November 1861

and designated Company C of the Twelfth Regiment.

Captain Kenan’s lieutenants were William A. Allen,

John W. Hinson and Thomas S. Watson.

Other North Carolinians serving with Capt. Kenan and

his Duplin men in the Twelfth Regiment were the

Catawba Rifles, Townesville (Granville) Guards,

Warren Rifles, Lumberton Guards, Granville Greys,

Cleveland Guards, Warren Guards, Halifax Light

Infantry, and the Nash (County) Boys.

Captain Kenan and his men accompanied the Twelfth

Regiment to Richmond in late May 1861, and moved to

Camp Arrington, Sewell’s Point, that November for

winter quarters and becoming part of General William

Mahone’s Brigade. On 18 November Company C was

mustered out and most re-enlisted into Company A,

Forty-third North Carolina Regiment. This new regiment

was comprised of men from Duplin, Mecklenburg, Union,

Wilson, Halifax, Warren and Anson counties.

The Forty-third Regiment was organized near Raleigh and

mustered into State service in March 1862 for three years

service or the duration of the war. Elected colonel was

Junius Daniel of Halifax, and Thomas S. Kenan elected

lieutenant-colonel.

The regiment was first ordered to Wilmington, then to

Fort Johnston under the command of General Samuel G.

French, Cape Fear District commander. With the threat

of Northern invasion again in May 1862, the Forty-third

Regiment was sent to Richmond near Drewry’s Bluff

on the James River.

After Daniel’s promotion to brigadier, Kenan was elevated

to colonel of the Forty-third Regiment; brother James G.

Kenan became captain of Company A (with Lieutenant

Stephen D. Farrior next in command) and younger brother

William Rand Kenan was appointed regimental Sergeant-Major.

The regiment was involved in engagements near Malvern Hill

and Drewry’s Bluff, then returned to North Carolina when

enemy advances from occupied New Bern threatened in

late 1862. Col. Kenan’s regiment remained at Kinston

in the spring of 1863 with action at Little Washington;

it returned to Virginia in June to become part of

Gen. Ewell’s Corps, Rodes Division in Lee’s Army

of Northern Virginia. There it prepared for

General Robert E. Lee’s Pennsylvania Campaign.

Gettysburg and Johnson’s Island

Colonel Kenan’s regiment saw brisk action at Gettysburg’s

Seminary Ridge and on the third day, at Culp’s Hill, where

Kenan received a severe leg wound and was incapacitated.

The regimental command was assumed by Lt-Col.

William Gaston Lewis of Rocky Mount.

During the after-battle lull Col. Kenan was captured by

the enemy as hospital wagons left Gettysburg; brother Captain

James G. Kenan was also captured. Thomas was sent to

Northern army hospitals in Maryland and then transferred

to the Johnson’s Island prison camp near Sandusky, Ohio.

His brother James ended up there as well.

For thirteen months “Their sufferings here during the winter

were very severe, with cruel guards, insufficient food, scanty

clothing, in houses neither ceiled or plastered, and with but one

stove for about sixty prisoners” (Sprunt, pg. 345). The search

for rats to consume for rations was an everyday occurrence,

and while there the Kenan brothers saw Lt. James I. Metts

of Wilmington “selected as one of the most enfeebled and

delicate of the prisoners” picked for exchange for a

Northern prisoner.

Lieutenant Metts

Author Michael D. Hayes writes of Johnson’s Island in his

“Prison-Pens of the North” that “The prisoners endured harsh

winters, food and fuel shortages, and disease. Research indicates

that close to 300 prisoners died on the island during the war.”

Captain E.D. Patterson of the Ninth Alabama Regiment,

confined with Kenan at Johnson’s Island recalled:

“No one who passed through the year 1864 in prison

there has forgotten, or ever will forget, the awful

suffering there – from cold and from hunger. I used to

[wonder how Northerners who hated the South so]

could look upon prison life and see men staggering about,

weak and hollow-eyed from hunger, searching in vain

in the slop barrels for scraps, and eating rats, to keep

soul and body together, [that] they would

have been satisfied”

(Confederate Veteran, Oct. 1900, pg. 443).

Though Northern prisons were surrounded by plentiful food

and medicines, they experienced a higher death rate among

prisoners than their Southern counterparts, which were surrounded

by famine and a naval blockade which prevented medicines

from entering the Confederacy.

In March 1865 Thomas and James were part of 300 Southern

officers paroled and sent to Richmond, records indicate that he

was not exchanged. Colonel Kenan traveled toward Greensboro

where General Joseph E. Johnston still had his army in the field

after Lee’s capitulation in Virginia. He continued to Charlotte

after Johnston’s surrender at Durham, and on 12 March 1865

he was officially paroled with Johnston’s army.

The Return to Kenansville

By 17 May he had returned to Kenansville and Liberty Hall,

an area relatively untouched by the destruction of war.

Guided by the family tradition of public service, he was a

successful candidate for the General Assembly in Raleigh and

served his district 1865-1867. A congressional candidate

in 1868, he failed election due to the radical Republican

regime in political control in North Carolina.

A New York Times article of 25 September 1868,

“Nominated for Congress,” stated:

“The Democratic Convention for the Second District of

North Carolina met at New Bern on this 17th, [instant],

and nominated Col. Thomas S. Kenan for Congress.”

Though defeated, Thomas had desired to “. . . seize that opportunity

to stir up the people of the District and publicly to denounce the mischievous and corrupt policy of the [Republican party].”

Thomas married Sallie Dortch of Edgecombe county, moving

with her to Wilson about 1869 where he was employed as an

attorney with the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad. With

him at the railroad was former Lt. Col William G. Lewis of

the Forty-third Regiment, who took command of Col.

Kenan’s regiment when he fell wounded.

Postwar Political Career

A politically-active resident of Wilson, Thomas was elected mayor

of the city with the assistance of influential politico Wharton Jackson

Green, who was wounded at Gettysburg like Kenan and was

imprisoned at Johnson’s. They were both strong supporters

of popular North Carolina Governor Zebulon Vance and were

perennial promoters of Southern veterans’ organizations

and memorial associations.

Vance

Mayor Kenan promoted economic development in Wilson

and postwar North Carolina, and in June, 1873 addressed

students at the Wilson Collegiate Institute on the importance

of a practical, industrial education for Southern men. Too long,

he reminded his audience, the South had sent young men

northward to learn the professions and that:

“the times now demanded this should cease to be so, that

our Southland was to built up and developed, rail roads and

factories were to be built and they must be built by Southern

men, and that, in order to do it, the mechanics of the

South must be educated men . . . “

Col. Kenan was keenly aware that the South’s four-year bid for independence was defeated by the industrial and material might

of the North, and that his native section needed to modernize

to protect itself in the future.

A proponent of higher education in North Carolina, Kenan helped

increase public support for the re-constituted University of

North Carolina which had closed its doors in 1871 rather than

be controlled by the carpetbag regime in Raleigh. This effort was

successful and the university re-open its doors in 1873 under

the control of North Carolinians.

In mid-1876 Col. Kenan sought public office again with the

Wilmington Morning Star publishing a personal sketch and stating

that he was “the worthy nominee for Attorney General on the

Democratic Conservative ticket.” The sketch added:

“There is an elevation of character about him and his family

seldom to be found anywhere, and only to be known to be

admired. I would to God that all men, everywhere, who in this

Centennial year aspire to an honored position, we such as

he, for peculation and thievery would know no place in their

hearts, and the people of this distracted country would once

more rejoice in honest constitutional government.”

The writer saw in men Col. Kenan’s character and integrity the

antidote to the venal and corrupt Reconstruction regimes and political

hope in the future of the State. He won the attorney-general race,

saw Zebulon Vance become governor once again, and witnessed

the withdrawal of Northern occupation troops which had

protected the Republican party in North Carolina.

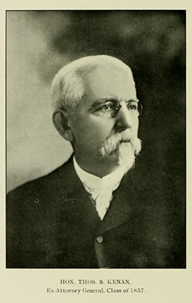

Kenan held the attorney-general’s office for eight years

(1877-1885) and built a home in Raleigh one block from the

Governor’s mansion, was appointed a trustee of the University

in 1883 (and member of its executive committee), and became

president of its Alumni Association.

On 1 March 1886 he was elected Clerk of the North Carolina

Supreme Court, serving in that capacity until his death. Col.

Kenan also served as president of the North Carolina

Bar Association.

Leaving a Legacy of Public Service and Education

Thomas was instrumental in establishing at the university the

Kenan Fund for acquiring books and other printed materials

relative to Southern culture, and focusing on the War and

Reconstruction. He was also a founding member of the

North Carolina Literary Society.

The last decade of the century saw Col. Kenan continuing his

public service and erecting memorials to Southern veterans of

the former Confederacy in Raleigh and elsewhere. He supported

the movement to erect a Soldiers’ Home in Raleigh for aged

veterans and served as a member of the Confederate

Memorial Association’s executive committee.

In 1895 Kenan contributed a history of his Forty-third Regiment

for the five-volume compilation of North Carolina’s military units

in the War, as well as his experiences as a prisoner at Johnson’s Island.

When the College of Medicine of the University of Virginia decided

to fill its Board of Trustees with distinguished men from the region,

Col. Thomas Kenan was selected to represent his State.

At the laying of the cornerstone for the Confederate Monument at

Raleigh, 22 May 1894, Col. Kenan spoke briefly to the assembled

citizens. He introduced the speaker, Hon. Risden Tyler. Bennett and

former colonel of the Thirteenth North Carolina Regiment

who said in part:

“The South, inspired by lofty ideals of duty and stimulated by

precious faith, has done well in preserving, amidst poverty

and toil, the wholesome truths of that great struggle.

The daughters and grand-daughters of the regiments that

followed the leadership of Lee and Jackson, Branch and

Bragg, upon the crested ridge amid the stormy presence of

Battle – the women of our State have “set up a stone

for a pillar,” to testify to unborn ages

our reverence for our dead.

If the courage of these Confederates, who stepped from their

homes into the army and were soldiers, was admirable, the

principle for which they contended cannot be overstated.

The right of local self-government lay at the very root of struggle

and conflict between the government and the Confederate States. These men had a just cause – they were dutiful sons of

indestructible States. Their actions were worthy of their

day, their achievements were worthy of all time.”

Col. Kenan secured from his wealthy relative and Florida developer

Henry Flagler (who married niece Mary Lily in 1901) a generous

donation toward Richmond’s “Battle Abbey” museum which would

exhibit the artifacts of all the former Confederate States, and highlight

the rich Southern culture within each State’s memorial room.

By 1911 he was feeling the strong effects of old age and the pressure

of his many public commitments. His health declining, Col. Kenan

died in his Raleigh residence two days before Christmas, 1911.

He is buried in that city’s Oakwood Cemetery.

Sources:

Sketch of the Forty-third Regiment, NC Troops, 1895,

Across Fortune’s Tracks, Walter E. Campbell, UNC Press, 1996

Chronicles of the Cape Fear, James Sprunt, 1916

Confederate Colonels, B. S. Allardice, University of Missouri Press, 2008

Biography of Thomas Stephen Kenan, A.M. Fountain, 1988

Prison-Pens of the North, Michael D. Hayes, Colson Printing, 2004

Experiences on Johnson’s Island, H.W. Henry, Confederate Veteran, December 1907

Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume Twenty-two, 1894

©2006 Cape Fear Historical Institute